Another blessing shared by tea lovers is the rich history that has been handed down to us by our predecessors.

It is transmitted in the form of rituals, writings, and treasured objects that have been preserved for our present enrichment, and to be passed down yet again.

In some circles, the highest form of tangible tea history is said to be the Ido chawan.

The Ido story begins in Korea, where potters made these rustic bowls for everyday use. Many say they were intended as rice bowls. The wheel-thrown shapes were rough; often uneven or showing finger marks.

Another sign of their humble beginnings are the wads of clay in the center of the bowl. This technique was used to stack several tea bowls together in order to fire a larger load, without allowing the glaze on the piled bowls to fuse together.

It is not clear when this style of pottery first became known in Japan, but by the time of Sen no Rikyu and his disciples, the bowls were touted as among the purest expression of their wabi esthetic, and highly prized by both the tea men and their patrons.

There were other types of Korai (Korean) bowls imported by the Japanese chajin, but Yamanoue Soji is credited with identifying the Ido bowl as the best among them. He even selected an Ido chawan for the collection of Toyotomi Hideyoshi.

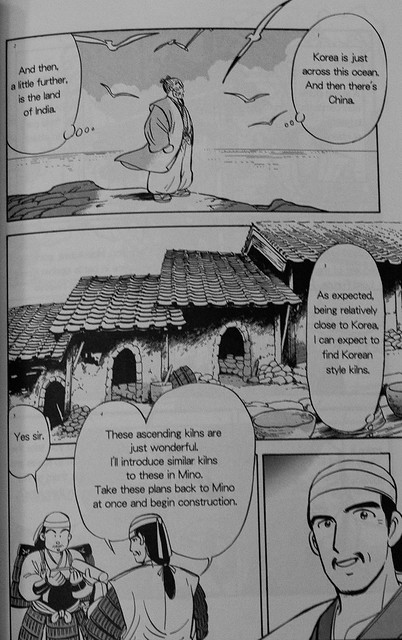

Another disciple of Rikyu, Oribe Furuta, sought inspiration from this pottery in order to infuse more of their wabi character into his own chawan designs.

Looking to get even closer to this ideal, he sought to understand the construction of the Korean climbing kilns, and recreate them in Japan.

Due to the rising popularity of the style, Japanese began making commissions to Korean potters or sending their own designs for teabowls to be fired in the climbing kilns. Unfortunately, with the chajin in service of the war thirsty Hideyoshi, this voluntary trade soon turned very bloody for the Koreans.

Hideyoshi had deluded himself into thinking that he could capture the many riches of China, if only Korea would guarantee him safe passage through their peninsula. When the Korean envoy rejected these terms, Hideyoshi pressed on to war anyway. He never reached China, but the Japanese army razed the settlements of Korea almost beyond repair. As a spoils of war, they returned with dozens of Korean potters as their captives, and set them to work back in Japan.

From that point on, the nation of Japan continued to toil at extracting the wabi essence of the Ido chawan, but the original is still considered the pinnacle of the form.

The chajin struggled with the idea of creating wabi, as making something that appeared to be without intention was naturally an intention itself. Perhaps the failure to surpass the character of the Ido chawan is proof that no amount of force (of will or military conquest) is capable of coercing real beauty.

Perhaps reaching for something and never quite grasping is part of what wabi is about, after all. One may never reach this state of imperfection perfectly, but while we ponder it, we have Ido to enjoy.

Further Reading

- Chanoyu Quarterly #18

- Dawan, Chawan, Chassbal

- Toki

- Warrior Tea Man (Manga)